We Need a Million More Black Jobs Before We Can Celebrate

The African-American unemployment rate has been trending downward for 6 years since 2011, so the fact that it reached a record low in December is not too surprising. It is also not surprising that Donald Trump chose to dismiss the trend for black unemployment under the Obama administration. Trump claimed that the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ jobs numbers were “phony” up until he became president, when he declared them “very real.”

While the unemployment rate is a useful measure, it is less useful for groups facing a persistently unfriendly labor market. In the wake of the Great Recession, the labor market was unfriendly to everyone, leading many to give up looking for work. Individuals who give up looking for work are technically not in the labor market, and they are not counted as unemployed in official statistics even though they are jobless. For this reason, the unemployment rate underestimates the problem of joblessness.

This underestimation is very significant for African American workers. These workers historically have experienced a very challenging labor market, due to the lack of investment in their communities and racial discrimination by employers. For black workers, the employment-to-population ratio is a better measure of the employment opportunities than the unemployment rate. The employment-to-population ratio simply measures the share of the working-age population that is employed. If a large proportion of a group has left the labor market due to hostile circumstances, then the group’s ratio will be reduced. When the economy is very strong, we see the employment-to-population ratio rise even for disadvantaged groups.

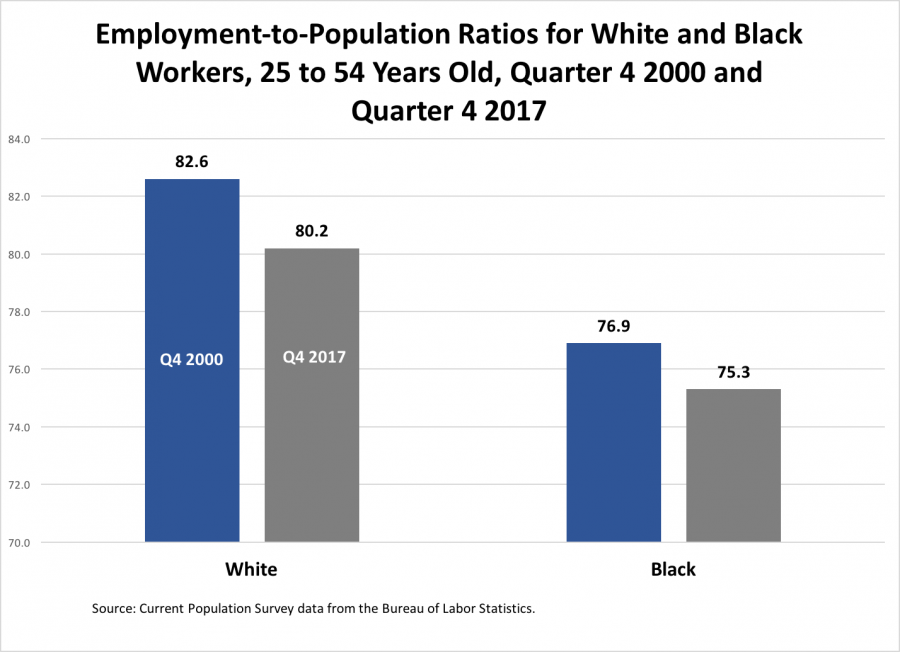

Looking at the employment-to-population ratios for prime age (25 to 54 year old) workers in the figure above, we see 2 things. First, the ratio from the last quarter of 2017 is lower than for the same quarter in 2000 for both white and black workers. By this measure, the job market still is not as good as we saw in 2000. Second, the black ratio is lower than the white ratio in both time periods. Even the black employment ratio in 2000, which was quite high for blacks, was still lower than the 2017 ratio for whites. Disinvestment and discrimination are the primary cause for these disparities.

In a very strong and racially fair economy, the black employment-to-population ratio today would be where the white ratio was in 2000. It would take 1.2 million more African Americans working for the black employment-to-population ratio to reach that level. When we have 1.2 million more black jobs, then we can celebrate the state of the American labor market.

An Important Anniversary

More than just jobs, it is important for workers to have good jobs and a voice in their workplace. Fifty years ago, black sanitation workers in Memphis began a strike for better safety standards, a decent wage, and recognition of their union. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis while supporting the strikers. This year the IAM2018 coalition is commemorating these events.

The coalition’s website reminds us of the incidents that precipitated the strike:

On February 1, 1968, Memphis sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker huddled in the back of their truck to seek shelter from a storm. Suddenly, the truck’s compactor malfunctioned, trapping Cole and Walker and crushing them to death.

The tragedy triggered the strike of the city’s 1,300 sanitation workers. They had warned the city about dangerous equipment but were ignored. They were fed up with poverty wages and racial discrimination. They walked off the job and marched under the banner: I AM A MAN.

On February 1, 2018, people across the country will observe a moment of silence to honor the memory and sacrifice of Echol Cole and Robert Walker. The coalition will also have a conference in April.

Today, a third of African-American workers earn poverty-level wages, and, in recent decades, there has been a steady decline in the black unionization rate. The struggle of the Memphis strike continues today.