Wage Theft vs. Shoplifting: Guess Who Goes to Jail?

If you want to make crime pay—and get a lighter penalty if you’re caught—you’re better off cheating your employees out of their fair wages than trying to nick the latest video game console or pair of designer shoes off the shelves of your local retailer. That’s the conclusion of my new Demos research brief, The Steal. And no, it’s not a how-to for aspiring criminals.

Instead, it’s a look at one way the American justice system is skewed in favor of power and privilege, treating the crimes of the powerful, such as stealing from employees’ paychecks, far more leniently than crimes committed by those with less power, such as shoplifting.

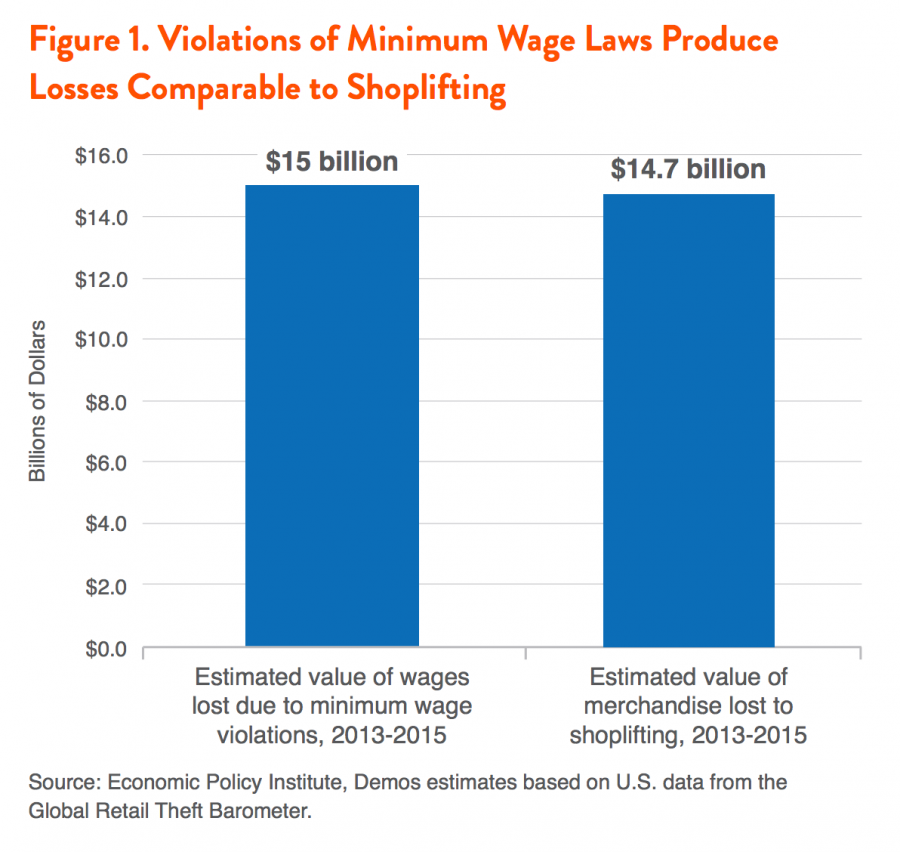

Drawing on data from a rigorous new study of minimum wage violations by David Cooper and Teresa Kroeger at the Economic Policy Institute, we compare the dollar value of shoplifting with the value of minimum wage violations, and find that they are roughly comparable. Each year between 2013 and 2015, retailers lost approximately $14.7 billion to shoplifting, while employers stole an estimated $15 billion through one form of wage theft alone: paying less than the legal minimum wage.

Minimum wage violations and shoplifting are crimes of similar scale, yet that’s where the similarities end. Despite the way that wage theft devastates working Americans and their families, pushes hundreds of thousands of people into poverty, robs states and cities of tax revenue, and places law-abiding businesses at a competitive disadvantage, we find that dramatically more resources go into detecting and deterring shoplifting than into preventing wage theft.

When wage thieves are caught, they also face a starkly different experience from shoplifters. If a shoplifter steals more than $2,500 in merchandise, he or she can face felony charges in any state in the country. Many states impose felony charges for stealing much less valuable merchandise. Yet criminal penalties of any kind are very rare when it comes to wage theft. Even when millions of dollars are stolen from employee paychecks, only mild civil penalties are applied under federal law.

The result is no surprise: unprincipled employers realize that the reward of stealing wages is greater than the risk of a slap on the wrist if they get caught. Not only are many large corporations serial violators of wage laws, many even continue to be awarded lucrative federal contracts after being penalized.

The disparity between the crimes of the powerful and those with less power is deeply linked to who the victims and perceived perpetrators are. Women, people of color, and immigrants, especially undocumented workers, are disproportionately likely to be victims of wage theft; a violation that disproportionately impacts them is allotted fewer resources for deterrence, investigation, and enforcement compared to shoplifting, and penalties are weaker. In contrast, even though shoplifting is committed by people of all ethnic and racial backgrounds, people of color, particularly African American consumers, are profiled as potential shoplifters, feeding into racial and ethnic disparities throughout the criminal justice system.

Efforts to create a more just system must focus on both sides of the equation. The nation must eliminate retail profiling and racial bias in the criminal justice system, but also place a far greater focus on deterring and penalizing the crimes of the powerful, including wage theft.